Interview with Susan Kemp: The Lynda Myles Project - A Manifesto

Still of The Lynda Myles Project: A Manifesto

English version article

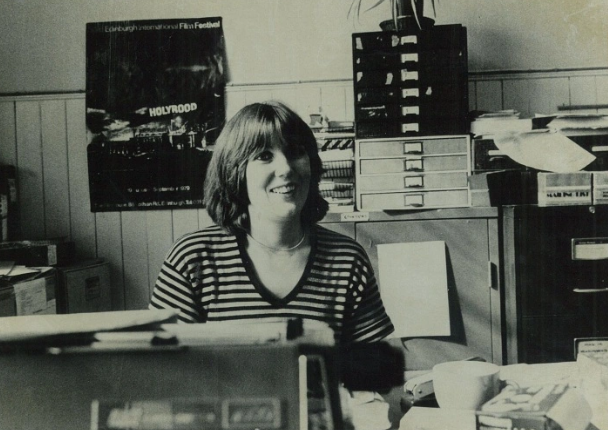

This year’s Edinburgh International Film Festival (EIFF), presents The Lynda Myles Project, a collaboration between Mark Cousins, Susan Kemp, and the curatorial collective inVISIBLEwomen, which rediscovers the works and contributions of Lynda Myles, the Festival Director of Edinburgh International Film Festival 1973-1980.

The documentary-in-progress, The Lynda Myles Project: A Manifesto, is an intimate and insightful portrait of Myles, and an essential work of cinephile activism. Meshing archival material with interview subjects including Jim Hickey and B. Ruby Rich, Kemp employs a series of provocations to tease out the philosophy behind a lifetime of ground-breaking film work.

The curation team of the Mint Chinese Film Festival invited Director Susan Kemp to share the process of this project, and about creative inspirations, collaborations and aesthetic approaches, their research approach and something about film culture and audience response.

For a bilingual interview article in Chinese and English, please subscribe to the official website of the Mint Chinese Film Festival (unicornscreening.com) and check it out in the ‘Media and Blogs’ section.

Question: Mint Chinese Film Festival – MINT

Answer: Susan Kemp – Susan

MINT: Congratulations on yesterday's screening of The Lynda Myles Project: A Manifesto. How was that?

Susan: Many people who know Lynda already were there, so there was a sense of a mix of people familiar with Lynda’s work and people less familiar with Lynda’s work. But at that point in the festival, you felt there was an energy that people wanted to talk about film festivals and this was a good spark for conversation. So, it was a kick response. It felt good.

MINT: During the launch event of The Lynda Myles Project: A Manifesto, we learnt that you have been inspired by Lynda Myles. Would you like to share the inspiration behind and what motivated you to create this documentary?

Lynda in EIFF credited Pako Mera

Susan: When I was in my twenties, I worked at the Edinburgh Film Festival in various capacities. At that time, I was really aware of people who had been at the festival for quite a long time already talking about Lynda Myles and her influence. It was a constant sort of sense of inspiration for the festival to think about the years when Lynda was director. Because, clearly, I think we all recognize that it was in her period of time director that the reputation for the festival was really established. What made it a recognizably important festival at that time in the film festival circuit was down to the work they’d done. As you know, since then there have been so many more film festivals, and the whole landscape has changed. Keeping in mind what she was saying seems even more important today. I think that for Edinburgh, given the troubles of the recent couple of years, for the festival, and also years before where it sort of lost its reputation and lost its sense of identity, it is a good time to be thinking: what is Edinburgh? One of the people who were in the audience said: ‘Edinburgh film festival can be the brain, you know, it can have that as its identity’. It used to have that as its identity. And I think, for me, Lynda Myles has always been the person who opens up the possibility that a film festival can within film culture more generally, and can operate as the brain.

MINT: We want to learn more about the collaborations. How did you find like-minded collaborators, Mark Cousins and inVISIBLEwomen, to work on this project, and how did you explore your relationship with Lynda and collaborators throughout the project development?

Project team members credit Shaoyang Wang

Susan: I have known Mark since we worked together at the Edinburgh Film Festival. He was director and I was a researcher and programmer. We have worked and known each other for a long time and worked on various projects. But one of the things we’ve often worked on together, which is of interest to you as well, is how we make women more visible within film culture more generally. So, we’ve done a couple of projects before and then we’ve both talked about too few people know about Lynda Myles. So, we’ve been talking about that for a while and then he suggested we make a film about her. The project sort of expanded and grew into two films. inVISIBLEwomen are graduates of the FEC program, their final project which I supervised was again, they did lots of detective work looking into the archives in Scotland and looking for the traces of women filmmakers. I’ve worked with them on quite a few projects since then as well. They’ve obviously got bigger and bigger and more involved in the sort of network. For them, working on a documentary was a departure from what they usually do but something they were really interested in doing.

MINT: A Manifesto suggests a strong political statement, and we would like to know more about your aesthetic approaches to convey the ideas of personal is political. First, the film is built and structured on your interview with Lynda Myles. Why did you choose to make the documentary based on the conversation with the character, and how did you set up this question?

Susan: One thing I’ve always really enjoyed as I get to know Lynda more is the conversation with her. I think this is part of her strength as a practitioner within film culture more generally, and what we all enjoy about film is the discussion, isn’t it? We could have done a more straightforward documentary which is either a biographical or historical narrative. Then I felt I would be dictating the history. I would be imprinting a summary of Lynda onto her rather than emerging from her. I felt that given Lynda’s greatest strength is her ability to talk about film with anybody, from the greatest, most famous filmmakers to the person on the street. She can make it interesting for anybody and so I wanted to build an aesthetic around that space of discussion. And also, there was another reason as well, which is that Lynda doesn’t like being filmed and she’s not the most comfortable person. So being in a relationship with her, between her and me, having a conversation was the best way to make her come across as herself to be relaxed and come across as the person I knew, which worked really.

MINT: When listening to Lynda Myles talking about her experiences and feeling, in addition to your voice appearances, I noticed that you are also mostly in front of the camera, showing half of your body. I wonder why you put yourself in the frame and how you relocate your position when making the film.

Susan: I collaborated with Katrina who shot the interview. Before shooting the interview, we wanted some sense of awareness that there’s somebody else in the room that this is being filmed. We didn’t want to remove that aspect of it. We wanted those rough edges. We wanted it to be about the relationships. So, the reason why I’m in shot often is to establish and remind people of the relationship. This isn’t just pointing at the camera on Lynda and expecting her to produce something, it is about me pulling things out of her and drawing things out of her. Therefore, it’s about the spatial relationship between her and me, and that sense of being in it together.

MINT: We also noticed that the documentary widely used archives ranging from newspapers, movies, images, printed email copies, documentation and personal photos. How did you select and produce this archival footage related to Edinburgh and why did you decide to remake these archival clips?

Susan: It’s a long process of research because in the National Library of Scotland, inVISIBLEwomen went to look at the books they have that are at the Edinburgh Film Festival. They’re not curators, so it’s very difficult to know what documents mean. They just gathered a lot of information about what was there. We didn’t know how useful it would be. We were aware that certain other materials were with the film festival, and we had permission from the film festival to access materials, but we hadn’t yet gone to the film festival office to see what was there. And then, it went into administration and we couldn’t access the material immediately. Lots of different things happened around that time which involved them eventually being taken to the National Library of Scotland. I eventually accessed them there, but in that period of time, we didn’t know what was available or what was there. There’s certain, as we’ve discussed with archive, when we looked at Sarah Polley’s film, for example, quite often there isn’t material, there isn’t anything. Also, the archive costs money, you have to license it. I’ve got a tiny amount of money. So, for me as well, it doesn’t need to be. When I was learning to make documentaries, as somebody once told me, you don’t need to be lord privy seal, which is a government position in politics is called lord privy seal. What they mean by that is when you talk about lord privy seal position, you don’t need to see a show picture of a lord up of the heads and then a seal. You don’t need to be too literal about your use of archive and actually being more abstract in your use of some remakes can give people space to just reflect and think. So, the photographs and archives of Lynda that show her when she was younger or in different situations really work with what she’s talking about. You don’t want everything to be directly related to what she’s talking about. That’s why I did some fake archive.

MINT: We definitely want to know more about the research process behind it. Would you like to discuss about your process for researching and gathering materials about Lynda Myles? Were there any particular challenges you faced during this process?

Susan: Yes, I think when you’re making a documentary that’s based on a relationship and a conversation, it’s an odd thing because you want to converse and talk to your main subject, but you don’t want to create the filming. You’ve got this really odd balance where you need to talk to them to find out and do some research around the points they make. But you don’t want to make them feel they’ve already told you things. So that when you’re filming them, they don’t tell you things that you want them to tell you. It’s a really odd balance. A lot of the research you do around that, you have conversations with your subject, but you don’t talk to them necessarily about everything you’re going to include in the interview. You read as much as possible and you look around what’s available in the time you have. That involves all the reading we do around scholarly work, film festivals, and film culture, having that knowledge. Then there’s the more direct research and articles and essays and anything written about Lynda Myles. Then, there are any interviews she’s previously done that we could access and look at. You’re gathering as much and then you’re talking to other people about Lynda as well. Mark and I would talk a lot about Lynda, and a lot of people I would talk to them about her. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, you’ll get one bit and then see where it fits with the other bit, and eventually, you’ll feel ready to do the interview. The interview is the final part of the research process.

MINT: How do you and the project team investigate archives related to Lynda Myles’s 1972 women’s event in EIFF? I really want to know how you select the talking heads did you involve Lynda Myles in the research process, and why it matters?

Susan: Yes, as you saw in the film, Lynda kept a lot of material herself. It was really interesting to see what she has. We looked through what she had beforehand. She’s got a lot of documentation around the women’s event, and in the National Library of Scotland as well. There’s a lot of documentation about the women’s event. So, it’s just a question of reading all that material, and then deciding which elements you want to talk about in the film. Because the film is very limited in time. You know it’s not quite the same as being able to write a long dissertation. You’ve got very limited time and it’s only one part of what you’re talking about. The inVISIBLEwomen Woman team found a letter from B. Ruby Rich in the archive, which created an impression of a really strong bond that they had. We very much admire B. Ruby Rich in her writings anyway. We thought it might be nice to talk to her and so it proved. Then Jim Hickey as well, because he had a really good understanding of her early years. We didn’t do too many more because I’ve done that in the past where you do lots and lots of interviews, but then everybody’s impression is different and it becomes about them rather than her. So, we chose to only do two, and two was enough.

MINT: In chapter two we noticed a lot of things about Myles’s feminism, critiques and theories of visual pleasure. Also, in my final project, I got the literature review about the feminism movement and feminism festivals. A lot of hints direct to Lynda Myles’s 1972 women’s event. So, how you think the form of the documentary can better convey the theme of a woman’s cinema and woman’s creativity that might beinteracted with feminism languages?

Susan: It’s interesting because in a documentary we can only talk about it in broad terms, which is again a reminder of folk, but the context that’s really interesting about how we remember and forget. The labor of women is not ever present in our discussions, we have to do these reminders so that we keep women’s labor and creativity as part of the discussion around film. If we don’t, it’s really interesting here, we just need to. Documentary can help us just remind us that we need to make sure that we’re doing the work to include women in their work in the conversation. I think it would be really well-balanced from a curatorial point of view. A documentary such as the Lynda Myles documentary would be really well balanced by showing a program of short films that is either of contemporary women filmmakers, or that also does a retrospective of the sort of filmmakers that they were showing in the women’s event in 1972. Lauren Clark is one of the inVISIBLEwomen Woman team, she had created a film festival with a friend in Glasgow called Femspectives. One year they did really detailed research about the films that were shown in the women’s festival. They tried to locate prints and copies and show them again. They found a lot of them were not possible to trace because we’d forgotten them. We hadn’t kept them present in our conscious. This is what is really interesting, not just the documentary on its own but the curatorial work that is inspired by it. Does it motivate people to go and look at those films, see what’s still available and can they be re-shown, to make sure that contemporary women’s films are shown and not forgotten? That balance I think is a call to action from programmers and curators.

MINT: Have you thought about the film will be starting its public screening before it finishes? Why did you decide to present your project’s work-in-progress version at the lastest EIFF? How do you expect or imagine a complete version will be exhibited and archived in the future?

Susan: The reason for showing it as a work in progress was because I had to make this film in my spare time. Obviously, my full-time job is teaching and there are other parts of life that get in the way. We are for a long time on a very small budget, so I had to do everything myself. I don’t know if I can get it finished in time. Once I showed a rough cut to the Edinburgh Film Festival and they were really enthusiastic about it. I really wanted to show the film at the festival, so we agreed to a work-in-progress screening. In the end, it was more finished than I thought it would be. There are only a few small things that I want to change now, and talking to the audiences afterwards, most of them didn’t think I needed to change much. I think I was the only one who noticed there were actually six chapters and there were two Chapter 4 in it. I need to sort things like that type of mistake that people hadn’t noticed but I noticed.

MINT: How do you hope the audience will explore from watching the film?

The Lynda Myles Project panel credit Shaoyang Wang

Susan: So, what Lizzie Francke said, she’s a former director of the Edinburgh festival for the last 15 years, she’s been working as an executive producer at the BFI funds in making feature films and very significant, important features and documentaries. She’s tapped into the network and she said it was the highlight of her festival, which was really key and really mattered. She said it’s an important discussion and it’s an important time for the discussion to be had about film culture more generally, and it sparks people’s thinking in a creative way. People who are interested in film culture will find it sparks discussion, which I think would be good. And people who are not so invested in film might find it generally interesting anyway because it’s a very interesting career but might not spark the same inspirational reaction.

MINT: I like your summaries in the last chapter, ‘we shall not cease from exploration and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.’ I want to ask about your opinions about how you see the film festivals and film culture in Edinburgh now compared to when the film festival was established.

Susan: I think it’s gone through a radical period where it’s been closed down and it re-emerged this year like a phoenix act of the flames as part of the international festival. I think Kate Taylor and the team Tamara Van Strijthem, Emma Boa, and all the team did a fantastic job this year. I really enjoyed the festival; did you enjoy the festival?

MINT: We really. We watched a Japanese film, THE FIRST SLAM DUNK, we loved it.

Susan: It was really good. The atmosphere was great. There were lots of really good talking points. There was this sense that as an identity the festival was bringing a new identity into play, which was the sense that it’s nurturing talent across generations. It’s not just new talent, it’s people who need support and the festival can give that sort of support. Also, revisiting the retrospective was really interesting in looking at provocative works and the impact provocative works have had on film culture. I think there’s a new voice of the Edinburgh Film Festival emerging if they build on it in terms of the thoughtful critical thinking that is going into what they’re doing, rather than just showing what they can get. I think that’s a really important change. Critically thinking effectively about how that film works in relation to that film in terms of the festival identity and the likely audiences, is something that hasn’t done enough recently. I think in the last 10 years, it’s just trying to show what it can get. It’s been a hodgepodge and a bit of a mess. This new direction is really interesting. I look forward to seeing how it goes and I think for future film festivals, the ability which film festivals once had, is to guide a certain excitement around film and to generate interest in a certain type of film. That’s even more important now, I think than ever. Independent cinema really needs film festivals and audiences really need film festivals too. I think it becomes even more important.

MINT: I felt encouraged after watching your documentary, and I am aware that the dominant culture might overlook the established female curator and producer, which is Lynda Myles. But there are also other females in the world who have been overlooked. I wish to invite you to share your vision of curating for identity, diversity and representation.

Susan: I think it’s about opportunities for people who are really engaged and interested is the most important thing. The inclusion of diversity starts much earlier, it needs to start where people thinking about where our interest is sparked in cinema, where we connect with it. It’s usually when we’re at a young age and then if you’re from disenfranchised communities, you might think ‘I will belong in that world even though I’m interested in it’. You might feel you’re not engaged or involved in it. My root incident was really interesting because I was working on a sort of community project in the video in Pilton and Edinburgh with disenfranchised communities making film projects, where they’re writing, directing, and making their own work. I met other people through that process who were also interested in cinema and interested in working in communities then moved from there into the film festival and started their career. That’s where it starts. It’s not when you’re in the centre of a cultural body like the film festival or film house, you can participate, but needs to start elsewhere and then you need to be open to those people coming in. If you’re in an underprivileged area of Edinburgh, and somebody creates a project where you can get involved in film out there, that’s the opening, isn’t it? Then people connect with that, also connect with you and they provide pathways into the more mainstream, more dominant and more seemingly privileged spaces. It’s about navigating into those spaces, but it’s not for everybody, and we shouldn’t assume it’s for everybody. We can’t impose what we find interesting onto the world at large and say: you must find it interesting too. That’s not the right way. Not the imposition, but the imputation.

MINT: What kind of support do Screen Scotland and the University of Edinburgh provide to this project and your cultural practices?

Susan: Rachel Hosker, who’s deputy head of the center for research collections at the University of Edinburgh, is very familiar with Lynda Myles’s contributions already. Also, she’s been working very hard to engage the library in Edinburgh and the collections with film. Because obviously, traditionally the library is a very old library and it is built from its relationship with more traditional scholarship texts and books. It’s a brilliant, fantastic library for that, but what we need to do is expand to other mediums and other forums. Rachel has been really instrumental in bringing film into the conversation. I felt that she might be somebody who was interested in this and sort of proved. They don’t have much money, so they gave us a small amount of money, then we needed Screen Scotland to get the additional money to pay for the licenses and the clearances. It’s very important, you can’t get that money from Screen Scotland unless you’ve got another funding partner. So, without the University of Edinburgh, we wouldn’t have been able to get the Screen Scotland money. It’s usually the case with these big public funding bodies. They won’t take the whole risk they only take a percentage of the risk. They don’t declare what percentage they will accept, but we were asking them for 85% of the budget, which is a lot for them. Normally they’d be happier with between 50% and 60% of the total risk. It’s been hard but we got there in the end. Wendy, our producer, she is fantastic and she just is relentless and keeps going until she gets it.

中文版专访文章:

专访苏珊·肯普:《琳达·迈尔斯项目:一份宣言》

《琳达·迈尔斯项目》是今年的爱丁堡国际电影节的特别活动之一,这是马克·考辛斯,苏珊·肯普和策展团体inVISIBLEwomen之间的合作,他们重新审视了1973-1980年爱丁堡国际电影节负责人琳达·迈尔斯的作品和贡献。

其中,正在进行的纪录片项目《琳达·迈尔斯项目:一份宣言》(The Lynda Myles Project: A Manifest,以下简称为《宣言》)是对迈尔斯的事迹深入而富有洞察力的探访,也是展现电影文化的重要作品。导演肯普坎普将档案资料与对吉姆-希基(Jim Hickey)和B-鲁比-里奇(B. Ruby Rich)等人的采访结合起来、揭示了迈尔斯一生中开创性电影工作背后的理念。

近日,薄荷紫华语电影节的策展团队邀请导演肯普分享了这个项目的过程、创作灵感、合作方式、美学方法和研究途径,以及一些涉及到关于电影文化和观众反馈的问题。更多中英文双语访谈文章,请订阅薄荷紫华语电影节官方网站(unicornscreening.com),并在 "媒体和博客" (Media and Blogs)栏目中查看。

问:薄荷紫华语电影节-薄荷紫

答:苏珊·肯普 (Susan Kemp)-肯普

《琳达·迈尔斯项目:一份宣言》剧照

薄荷紫:昨天《宣言》进行了放映。恭喜您!可以分享一些感受吗?

肯普:放映现场有很多已经熟悉琳达的人,还有一些不太熟悉她作品的人,我能感觉到在电影节独特的那种能量,人们想要谈论电影,琳达的事迹是一个很好的切入点,我感觉很棒。

薄荷紫:在《宣言》的发布会上,您提到您受到了迈尔斯的影响与启发。可以分享一下这部纪录片的灵感来源和创作动力吗?

迈尔斯在爱丁堡国际电影节 (摄影:Pako Mera)

肯普:我二十多岁时在爱丁堡电影节从事了不同工作。那时,在这个电影节待了很长时间的人就已经在谈论迈尔斯和她的影响了。迈尔斯作为爱丁堡电影节负责人的那些年长久以来滋养着这个电影节。因为我们清楚地认识到,是在迈尔斯负责时期,爱丁堡电影节的声誉才真正建立起来;是他们那时的努力让爱丁堡电影节在当时脱颖而出。自那时以来,电影节数量已经大幅增加,整个环境也发生了变化。将迈尔斯的话牢记于心在当下显得格外重要。考虑到爱丁堡近年来面临的困境,以及爱丁堡电影节在之前声誉受损、特性消失的情况,现在正是思考“爱丁堡意味着什么”的好时机。有位观众说:“爱丁堡电影节可以是类似人类大脑的存在,它可以以此为特点。”爱丁堡电影节曾经就是这样的。对我而言,迈尔斯一直都是那个拓宽可能性的人,是她让我意识到电影节可以在普遍意义上的电影文化中担任大脑的角色。

薄荷紫:下个问题我们来聊一聊与《宣言》相关的合作。您是如何找到志同道合的合作伙伴来共同完成这个项目的,比如马克·卡辛思(Mark Cousins)和inVISIBLEwomen这个组织?您又是如何在制作电影的过程中探索您与迈尔斯,及您与您合作伙伴间的关系的?

项目成员合照(摄影:王少阳)

肯普:我和卡辛思是之前在爱丁堡电影节工作时认识的。当时他是影节负责人,我在做研究和策划。我们相识很久,合作过许多不同的项目,其中有不少是致力于让女性在普遍意义上的电影文化中不再被迫隐身。这也是你感兴趣的东西。我们做了一些相关的项目,然后我们聊到迈尔斯,没有多少人知道她。我们就此探讨了一段时间,他建议我拍一部关于迈尔斯的电影。这个想法最后延伸出了两部电影。inVISIBLEwomen是由爱丁堡大学电影、展览与策展硕士项目的毕业生创办的。这是他们的毕业设计,也是由我指导的。他们查阅了许多苏格兰的档案去寻找女性电影制作者的痕迹。之后我和他们又合作了很多项目。这个组织不断壮大,也越来越活跃。inVISIBLEwomen通常不涉及纪录片,但对此也很感兴趣。

薄荷紫:我们还想了解您在《宣言》中采取的美学方法。“宣言”是个政治意味很强的词。您能讲讲您是如何在影片中传达“个人的即政治的”这一思想的吗?首先,《宣言》是基于您对迈尔斯的采访,也是由这些采访构成的。您为什么选择以对话的形式制作这部纪录片?您又是如何设计采访问题的呢?

肯普:在和迈尔斯逐渐熟悉的过程中,我很享受和她的交谈。她这种能力是她在普遍意义上的电影文化领域从业的优势。人们喜欢电影不就是喜欢讨论电影吗?我们本来可以以传记形式或按历史叙述拍一部更简单直接的纪录片。但那样我会觉得我只是在记录历史。我只是把一份关于迈尔斯的总结摁在她身上,而不是让总结自然生成。因为迈尔斯最大的优点是她能和任何人聊电影,不管对方是最伟大、最著名的电影制作人还是街上的普通人。她可以让任何人对电影产生兴趣。所以我想以讨论所处的空间为中心构建一种审美。还有一个原因。迈尔斯不喜欢被拍摄。她在摄影机前会感觉不舒服。我们两个处在一个讨论的关系中是让她能自然轻松地呈现自己、呈现出我所了解的那个人最好的方式。这样出来的效果非常好。

薄荷紫:当迈尔斯谈到她的经历与感受时,除了您的声音外,您也经常处在摄影机之前。观众可以看到您一半的身体。是出于什么原因让您选择出镜呢?在拍这部纪录片的过程中,您又是如何调整自己的位置的呢?

肯普:卡特里娜(Katrina)是采访部分的摄影师。在拍摄之前,我们就希望让观众意识到房间里被拍摄的除了迈尔斯还有其他人。我们想保留这些粗糙的部分。我们想要展现的是关系。所以,我也在画面里是为了建立并提醒观众这种关系。拍这部纪录片并不只是把摄影机对准迈尔斯并期待她自己展现出什么。重要的是,我要引导她去表达。因此,《宣言》是关于她和我之间空间关系的一部纪录片,有一种我们一起参与其中的感觉。

薄荷紫:我们还注意到这部纪录片使用了多种多样的档案资料,如报纸、电影、图片、打印出的电子邮件副本、文件和个人照片。您是如何选择与制作这些与爱丁堡相关的档案素材的?您又是为什么决定对这些素材进行一个再制作呢?

肯普:研究档案资料花费了很长时间。inVISIBLEwomen的团队去苏格兰国家图书馆查阅了一些有关爱丁堡电影节的书。他们不是策展人,所以很难明白那些材料意味着什么。所以他们只是收集了图书馆里有的信息。我们当时不知道那些资料有什么用。我们还意识到电影节方面也有一些材料。我们得到了查看这些材料的许可,但当时并没有到那边去看到底有什么。之后,电影节进入破产管理程序,我们没办法立即获取材料。那段时间发生了很多事情,最终这些材料被送到了苏格兰国家图书馆。我也是到那里才看到它们。但当时我们并不知道有什么可用的或者那里有什么。打个比方,我们在看萨拉·波莉(Sarah Polley,加拿大演员、导演、编剧)的纪录片时会经常发现里面没有材料,什么都没有。这就是我们研究档案时思考的问题。另外,档案需要付费,你必须获得许可。我的预算非常有限。所以对我来说,有些钱不一定要花。我学习制作纪录片时有人告诉我,你不需要成为掌玺大臣(英国政府中的一个职位)。这句话的意思是,当你提到掌玺大臣时,你不一定要看到一个贵族头像和一个印信。回到档案使用上,我们在使用档案时不需要过于追求直接相关性,实际上,更抽象的档案重制可以给人们提供回味和思考的空间。迈尔斯在年轻时或在不同情境下留下的照片和档案与她谈到的内容非常契合。你也不希望片子里出现的所有档案都与她谈论的内容直接相关。这也是我虚构了一些档案的原因。

薄荷紫:我们还想对影片背后的研究过程了解更多。您愿意谈一谈您收集、研究和迈尔斯相关的材料的过程吗?其中有没有遇到特殊的挑战呢?

肯普:有的。当你想拍一部以关系和对话为基础的纪录片时,情况会有些棘手。因为你想和你的主要受访者交谈,但又不想主导整个拍摄。这时就需要一种奇妙的平衡。你既需要和受访者交流,找出他们想表达的是什么,做一些研究,同时你又不想让他们感觉你已经什么都知道了。否则,你在拍摄时就不能让他们讲出你想要的东西。这种平衡很难把握。你会做很多调查和研究,你也会和受访者交流,但你不需要和他们讨论你准备放在采访里的所有内容。你要尽量多查阅资料,想一想在有限的时间能做什么。可看的东西有很多:学术资料,和电影节、电影文化相关的资料等等。这些知识是需要具备的。就《宣言》而言,除上述材料,和迈尔斯直接相关的研究、文章、论文等也有很多。此外还有她之前接受过的我们可以找到的所有采访。你得收集足够多的信息,然后去和其他人讨论迈尔斯。我和卡辛思会就迈尔斯聊很多东西。我也会和其他很多人聊她。这就像拼图一样。你找到一片拼图,然后去看它和哪一片是能拼在一起的。最后,你会感觉做好了采访迈尔斯本人的准备。采访她本人是研究的最后一步。

薄荷紫:您和您的团队是怎么研究与迈尔斯在1972年爱丁堡电影节举办的女性周活动相关的档案的?我对你如何选择采访对象很感兴趣。另外,您是如何邀请到迈尔斯参与档案研究的?她的参与在您看来有什么意义呢?

肯普:正如你在《宣言》里看到的,迈尔斯自己保存了很多资料。查阅那些资料非常有趣,我们事先看过。她有很多关于女性周活动的文件,这类文件苏格兰国家图书馆也有,总共有很多。所以,问题只在于要阅读所有材料且要选出哪些要放在纪录片里。一部电影时间极为有限,能涵盖的内容比一份专题论文少太多了。你讲不了多少东西。inVISIBLEwomen的团队在档案中找到了一封来自美国电影评论家B·鲁比·瑞奇(B. Ruby Rich)的信件。这封信展现出瑞奇和迈尔斯非常紧密的关系。我们十分欣赏瑞奇的写作。所以我们当时想着和她聊一聊会是个好选择。事实也证明如此。还有吉姆·希基(Jim Hickey)。他对迈尔斯早年的经历很了解。我们没有做太多这样的采访。因为我以前这样做过,结果是做了太多采访后,因为每个人对主角的印象不同,影片就不再是关于原来的主角,而是关于那些受访者了。在拍摄《宣言》时,我们只做了和瑞奇及希基的采访。我觉得这两个就够了。

薄荷紫:在《宣言》第二章中,我们注意到有许多关于迈尔斯的女性主义主张、批评文章和视觉快感理论的内容。在进行我的硕士项目时,我写了一份关于女性主义运动和女性主义电影节的文献综述。里面有许多内容指向了迈尔斯在1972年举办的女性周活动。对于纪录片能更好表达女性电影、女性创造这些可以与女性主义语言互动的主题的观点,您怎么看呢?

肯普:这个问题很有趣。在纪录片中,我们只能宽泛地讨论问题,只能起到提醒的作用。但我们记忆与遗忘的环境背景非常有意思。女性劳动在讨论中有时会消失。我们必须要做类似纪录片的提醒,确保将女性劳动与女性创造力纳入围绕电影的相关讨论。我们需要这样做。纪录片可以帮助我们提醒自己这一点。从策展的角度看,我认为这样会达到一种平衡。类似《宣言》的纪录片可以通过呈现一系列由当代女性电影制作人拍摄的短片,或者通过回顾在1972年女性周活动中放映的作品,达到很好的平衡。劳伦·克拉克(Lauren Clark)是inVISIBLEwomen的一员。她与她在格拉斯哥的一个朋友一起创办了一个叫Femspectives的电影节。有一年,他们详细研究了在女性电影节上放映的电影,试图找到那些电影的拷贝件并进行重映,但发现很多电影已经找不到了。因为我们已经把它们忘了,我们没把它们保存在意识里。提醒这种记忆与遗忘的纪录片本身,以及受其启发的策展工作都是很有趣的。纪录片会不会推动人们去观看那些快被遗忘的电影,去查看我们现在还有些什么,它们还能不能放映,去确保当代女性电影能够有展示的机会且不被遗忘?我认为纪录片能达到的这种平衡是对策划者、策展人的号召。

薄荷紫:您之前是否想过这部电影会在完成之前就进行公映?您又为什么会选择在最新一届的爱丁堡电影节上呈现一个未完成版本呢?另外,您有想过这部电影完成后会怎样吗,比如在展览、存档这些方面?

肯普:放映未完成版本是因为我全职教书,只能在业余时间拍摄制作这部电影。除了教书,我的生活中还有其他事情会影响这部电影的进度。很长一段时间,《宣言》的预算都非常少。我什么事都要亲力亲为。我也不知道电影能不能按时完成。爱丁堡电影节方面看过《宣言》的粗剪版后非常激动。我也很想在这个电影节上放映《宣言》。所以我们就决定做一个未完成版的放映。最后的放映版没有我想的那么粗糙。只有一些小的地方是我现在想做改动的。我和观众交流时,他们很多也说没有太多要改的地方。我感觉我是唯一一个注意到电影实际有六个章节,其中有两个“第四章”的人。我需要改正这种人们没有注意到但我注意到的错误。

薄荷紫:您希望通过观看这部电影观众能够探索些什么呢?

研讨会现场(摄影:王少阳)

肯普:我想借用莉兹·富朗开(Lizzie Francke)的话。她是过去十五年爱丁堡电影节的负责人。她也一直在英国电影协会(BFI)担任执行制片人,资助有重要意义的剧情片和纪录片。用她在这个话题的话讲,《宣言》是这次爱丁堡电影节的亮点,很关键、很重要。她说,现在是对普遍意义上的电影文化进行讨论的重要时刻,《宣言》就是这样的讨论,它让人们以创造性的方式思考。对电影文化感兴趣的人会觉得《宣言》引发讨论,这很好。那些对电影没那么感兴趣的人可能也会觉得这部纪录片有意思,尽管他们的反应会和“电影迷”们不同。

薄荷紫:我喜欢您在电影最后一章的总结,“我们不会停止探索,最终我们会回到起点并以全新的方式认识它”。那对于现在的爱丁堡电影节和爱丁堡的电影文化,和爱丁堡电影节建立时相比,您有什么看法呢?

肯普:爱丁堡电影节算是经历了大起大落。它之前被迫暂停,今年作为爱丁堡国际艺术节的一部分重启,就像凤凰涅槃。凯特·泰勒(Kate Taylor,爱丁堡电影节现负责人)、塔玛拉·范·斯特里杰姆(Tamara Van Strijthem)、艾玛·博亚(Emma Boa),以及电影节团队的所有人今年都做得极好。我很享受这个电影节,你呢?

薄荷紫:非常享受!我们看了灌篮高手剧场版,我们都很喜欢。

肯普:那太好了。爱丁堡电影节的氛围非常好。有很多可以讨论的点。我感到它有了新的特性,它在培养跨代人才,不仅是新人才,而是需要支持而爱丁堡电影节恰可以提供支持的那些人。另外,回顾那些充满挑战性的作品并思考它们对电影文化的影响很有意思。我认为,如果爱丁堡电影节在批判性思考这个方向继续发展,而非只是呈现电影节能收到的作品,爱丁堡电影节会焕发新生。这个改变很重要。对电影在电影节特性和潜在观众方面作用的有效批判思考还不够。过去十年,爱丁堡电影节只是在努力呈现它能呈现的作品,成了一个大杂烩,变得有点混乱。现在这个新方向很有趣。我很期待它的发展。未来的电影节需要有引导人们对电影产生兴趣和激情的能力。这比以往任何时候都要重要。独立电影需要电影节,观众也需要电影节。电影节变得越来越重要了。

薄荷紫:我看完《宣言》后倍受鼓舞。我意识到主流文化可能会忽视像迈尔斯这样杰出的女性策展人和制片人。世界上还有其他被忽视的女性。能不能请您分享一下您对策展在身份、多样性和代表性方面的愿景?

肯普:我认为最重要的是为那些真正把自己投入某项事业、对其感兴趣的人提供机会。对多样性的包容应该更早开始,从人们思考我们的兴趣是被电影的哪些特质所激发的、我们如何与之产生联系开始。这通常发生在我们年轻的时候。如果你来自权益受损的社区,你可能会觉得“即使我对电影感兴趣,我也无法摆脱弱势的状态“。你还可能感觉自己没有真正融入或参与到电影中去。我与此相关的经历很有趣。我曾在皮尔顿(英格兰一村庄)及爱丁堡和权益未得到完全保障的社区一起开展电影项目。社区居民自编自导,制作自己的作品。过程中我认识了其他对电影感兴趣并有志于在社区工作的人们。之后他们去到了电影节,在那里开始了他们的事业。对他们来说,那些权益受损的社区是起点。并不是你得身处电影节或电影院这样的电影文化核心才能参与到电影中。你需要在其他地方开始,然后对其他人的加入保持开放的态度。如果你身处爱丁堡的一个贫困地区,有人创建了一个项目让你可以参与电影制作,那不就是一个机会吗?人们通过这个项目与彼此相连,也为进入更主流、更主要的领域和看似仅限特权阶层的领域提供途径。这是个方法,但并不对每个人都适用,我们也不应该假设这一点。我们不能把我们感兴趣的东西强加给世界上的其他人,说,“你必须也得觉得有趣。”这不是正确的做法。

薄荷紫:请问Screen Scotland(国家机构,以提供资金和战略支持的方式,推动苏格兰电影电视产业各方面的发展)和爱丁堡大学为您这个拍摄项目和文化实践提供了哪些支持?

肯普:爱丁堡大学研究收藏中心副主任瑞秋·霍斯克(Rachel Hosker)本身就非常熟悉迈尔斯的贡献。此外,她一直在努力将爱丁堡大学的图书馆和收藏品与电影联系起来。那所图书馆历史很悠久,是由其与传统学术文献和书籍的关系建设起来的。从传统意义来讲,那个图书馆非常出色、非常好。但我们需要拓展它与其他媒体、领域的互动。霍斯克一直在推动将电影纳入讨论。我觉得她可能会对《宣言》这个项目感兴趣,事实也证明如此。爱丁堡大学资金不多,所以我们只拿到了一小笔钱。之后我们去找Screen Scotland,看它能不能给我们取得各种许可的钱。爱丁堡大学的支持在这时显得极其重要。如果没有其他资助方,你没办法从Screen Scotland获得资金。所以没有爱丁堡大学的帮助,我们就无法拿到钱。大型公共资助机构基本都是这样,只会承担一部分风险,也不会公开愿意资助多少金额。我们申请它们资助我们预算的85%,这已经算很多了。通常它们只愿接受50%到60%。申请的过程不简单,但最后我们成功了。我们的制片人温迪(Wendy)非常棒,她不达目标誓不罢休。

鸣谢(acknowledgement)

受访嘉宾(interviewee):导演 苏珊·肯普 (Susan Kemp)

采访人(interviewer):策展人 林怡翔 (Yixiang Shirley.Lin)

文章翻译(translator):王颖洁 (Yingjie Wang)

专访编辑(article editor):张紫略 (Zilue Zhang)

第二届电影节预告:

薄荷紫主创成员及策展团队正在积极筹备全新的电影节目、展映单元、产业论坛、创意工坊等线下线上影节活动,并计划面向广大海内外媒体和新兴华语策展人开放限量免费影节认证。薄荷紫新竞赛板块全球征片预计在9月底启动,现已邀请数位国际知名电影人、视觉艺术家、及文化专家加入评审团,届时将面向全球华语长片和短片创作者以及华人华裔影人进行征稿,敬请期待。新一届全球征集相关信息请持续关注影节官网和公众号(游霓映象),欢迎访问官网相关界面查阅往期全球征集令。

更多精彩内容,请订阅薄荷紫影节官网,关注游霓映象公众号!

关于薄荷紫华语电影节:

薄荷紫华语电影节是英国首个由女性组织的华语主题影节,由新锐电影策展人林怡翔(Yixiang Shirley Lin)和阿罕布拉影院主理人卡罗尔雷尼(Dr Carol Rennie)共同创立,聚焦华语电影的跨文化交流和女性形象的银幕再现。薄荷紫华语电影节近日正式于英国注册为社会利益公司。作为全年度活跃的影节,薄荷紫不仅在凯西克阿罕布拉影院举办年度华语电影节,还积极在英国各地和全球其他地区策划组织拓展电影展映和相关文化艺术活动。薄荷紫旨在为为未被充分代表的声音、形象和故事进行策展,积极挖掘并支持新锐女性、多元(非二元、跨性别)和酷儿导演,意在将独立先锋的优质华语电影和其他文化艺术作品(尤其是女性作品)推介至鲜少有机会接触华语电影及文化的地区,以承担作为英国第一个由女性组织筹办的华语电影节的文化及艺术责任。

首届薄荷紫华语电影节已于2023年2月5日于英国北部湖区坎布里亚郡的凯瑟克阿罕布拉电影院(Keswick Alhambra Cinema)落幕。首届影节取得了巨大成功,入场人数超过 1000 人次,其中 75% 为华人(裔),70% 为女性/性别非二元。截止至今日,薄荷紫已在伦敦、巴黎、北京等地合作策划举办了多场特别电影展映及巡回展览。

缘起于英国美丽湖区的薄荷紫华语电影节立足华人文化,力求探索华语电影的创意策展形式,重拾文化身份与价值,让华语电影触及当地社群、年轻观众、各界影迷与国际创作者,促进多元电影文化的传播与交流。此外,薄荷紫关注‘女性电影’(women' s cinemas)与女性电影从业者现状,借助影像中的女性再现社会性议题,期望建立国际电影产业中的亚洲女性代表和话语空间。在首届影展全球公开征片中,影节组委会收到超过400份作品,其中来自女性报名者的占总数量36.4%,男性报名者占57.8%,其TA/性别非二元报名者占5.8%。秉持着一种独立而开放的策展精神,薄荷紫希望通过电影这一包罗万象的形式,在创意策展的实践中,从女性主创们以及当代电影创作者们的视角向世界观众传递华人文化内涵。

往届影展

首届薄荷紫华语电影节已于2023年2月5日在凯西克阿罕布拉电影节成功落幕