Chris Berry‘s review : Snow Leopard (གངས་གཟིག, 雪豹, Pema Tseden, 2023): Beyond the Human-Animal Divide

Author: Chris Berry, King’s College London

English version article

Snow Leopard is an extraordinary vision of human relations with other animals. More specifically, it sets out the complex dynamics of animal conservation and Tibetan-Chinese relations in the People’s Republic of China today in an exciting and sometimes confronting story. A local Tibetan television crew, composed of three Tibetans and a Han Chinese cameraperson eagerly learning Tibetan, cover a breaking story about a snow leopard captured by a local herder after it has killed nine of his rams. The herder wants to kill what he refers to as ‘the beast’. His father argues that killing sheep is in the leopard’s nature, and that killing it will store up bad karma. Local officials and later the police arrive, insisting that the leopard is top of the national protected species list and must be released. And then there is ‘Snow Leopard Monk’, brother of the angry herder. Fascinated by photographing wildlife, it turns out he has a special relationship with this particular snow leopard.

Snow Leopard does not shy away from the leopard’s carnivore nature. This makes it a more challenging conservation story than, for example, Lu Chuan’s 2004 hit, Kekexili (可可西里), about saving cute and cuddly antelopes from poachers. Faster paced and more gripping than his earlier films, Snow Leopard also marks a number of new directions for Pema. First and foremost, the snow leopard would not exist without the extensive use of CGI. From The Silent Holy Stones (ལྷང་འཇགས་ཀྱི་མ་ཎི་རྡོ་འབུམ།, 静静的嘛呢石, 2002) to Tharlo (ཐར་ལོ།, 塔洛2015), he established a strong commitment to realism, an aesthetic that normally precludes CGI. Pema stated often that in his earlier work he wanted to put a Tibet he could recognize on film. He felt that he had grown up surrounded by outsiders’ depictions that were full of inaccuracies, whether they were full of idealizing Shangri-la imagery or demonizing stories about ‘feudal theocracy’. He filmed on location, using local people speaking their local dialects and living the complex mix of the modern and the traditional that characterized the Tibetan regions of the People’s Republic of China. The leap to CGI in Snow Leopard shows a willingness to explore new technologies and new aesthetics.

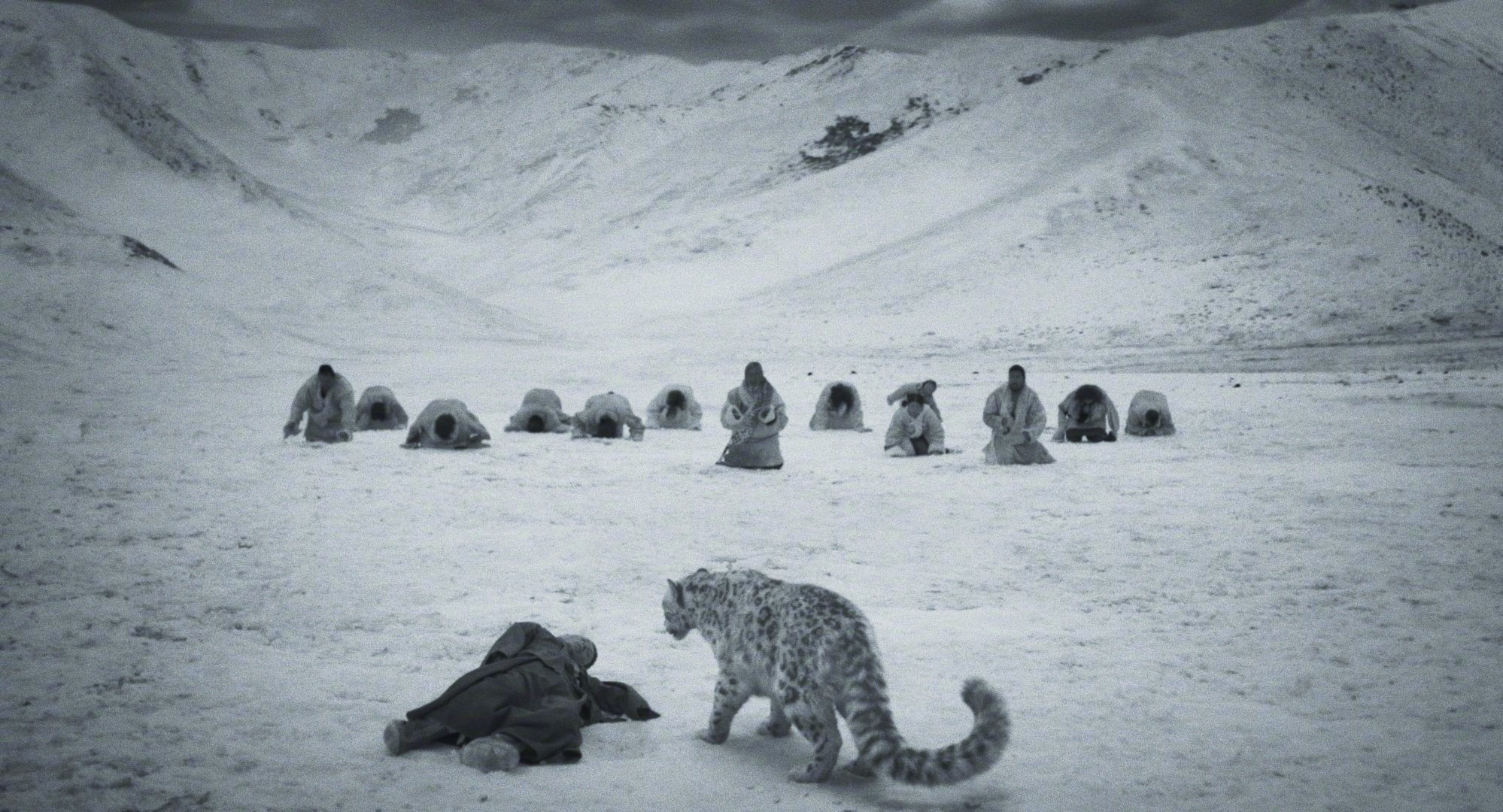

The second big shift in Snow Leopard lies in the use of dreams, memories, and visions. If his early films focused on getting the look of the external Tibetan world right, with the two films he made before Snow Leopard, he had already turned his attention to the internal Tibetan world. In Jinpa (ལག་དམར, 撞死了一只羊, 2018) and Balloon (དབུགས་ལྒང་།, 气球, 2019), it is not always clear if the visions we are seeing are those of one character or shared. Tibetan culture as depicted in Pema’s films is one where reincarnation is taken for granted; characters often ask if a certain child could be a reincarnation of someone who died not long ago. So, perhaps this blurring between subjectivities and sense of sharing subjectivity is also part of the Tibetan internal world. In Snow Leopard, Pema’s big innovation is the bond between the snow leopard monk and the snow leopard itself. The film takes us into a space of shared memories and subjective visions between the human and other animals. Given the Buddhist belief that souls transmigrate between different kinds of sentient beings, this is also part his cinematic rendering of the internal Tibetan cultural world.

Third, Snow Leopard deals with the complexities and tensions of Tibetan contemporary life within the People’s Republic of China more fully and frankly than ever before in Pema’s films. As China’s first Tibetan feature filmmaker, and fully aware of the extreme sensitivity of everything to do with Tibet, Pema has always trodden carefully to get his films through the Film Bureau’s censorship. Early on, he avoided Tibetan-Chinese encounters in his films as much as possible. Challenged, he would say his films were set several years ago, in places where there were few Han Chinese. In Balloon he had already moved into more sensitive territory by touching on birth control policies and their effects. But, as in his other films, all the main characters were Tibetan, including people in authority, and almost the whole film was spoken in Tibetan.

Snow Leopard embarks on a different journey with a title card that gives a recent and specific date – 2016. The long opening journey with the TV crew in the SUV might remind some audiences of his earlier film, The Search (འཚོལ།, 寻找智美更登, 2007), but it is also strikingly different, because we hear a mix of Tibetan and Mandarin Chinese being spoken from the outset. Although the cameraperson wants to learn Tibetan, he is still a beginner, unlike his Tibetan colleagues, who have had to learn Mandarin from an early age and can communicate with him easily enough.

Snow Leopard is full of tensions. But, despite the mix of Tibetan and Han Chinese characters, those tensions are not ethnic. Rather they mark out different understandings of the world. The government officials and the police are a mix of Tibetans and Han Chinese, and they are there to ensure that the law on animal protection is upheld. The older brother who wants to kill the leopard is concerned primarily with economic loss; if he is compensated for the rams, he will let the leopard live. But it is the father and the monk who articulate a different logic, less concerned with immediate material or legal issues, but instead focused on the ethics of the human relationship with other animals and sustaining the life world they both inhabit. In this respect, Snow Leopard not only communicates a Tibetan cultural logic but is strikingly in tune with the contemporary survival crisis of the Anthropocene era.

Snow Leopard confirms that Pema Tseden’s was at the height of his power, confident in taking new narrative and formal risk. However, tragically he died 8 May 2023 at the age of only 53, before the film’s release. The full story of what happened is not clear, but one version I have heard suggests he may have suffered altitude sickness while location scouting for his next film, which in turn brought on a fatal heart attack. Ironically, Snow Leopard has many moments where characters gasp for breath as they climb high peaks or need oxygen boosts at high altitude. There are rumours that perhaps enough material for one more film exists. But if Snow Leopard is Pema’s last film, it certainly confirms the magnitude of our loss.

Screening information:

In memory of the contemporary Chinese film master Pema Tseden, we will present a special screening of his posthumous work, 'Snow Leopard' (གངས་གཟིག, 雪豹, 2023) on Saturday, Feb 3, at 20:00, at Keswick Alhambra Cinema. We’ve invited Professor Chris Berry from King’s College London to record a video to discuss about our film selection and we will play it during the panel discussion before this screening.

中文版文章:《雪豹》(གངས་གཟིག,万玛才旦,2023):人兽关系之外

作者:裴开瑞(Chris Berry),伦敦国王学院

翻译:王颖洁

《雪豹》极为出色地讨论了人类与其他动物之间的关系。具体而言,电影呈现了当今中华人民共和国动物保护和藏汉关系中的复杂态势,故事动人心弦且不时引人深思。《雪豹》围绕当地藏语电视摄制组对一起突发事件的报道展开。摄制组一行四人,包括三名藏人和一名热心学习藏语的汉族摄影师。他们要报道一头雪豹咬死牧民九只羯羊后被捕获的事。损失羯羊的牧民想打死雪豹,也就是他口中的“畜牲”。牧民的父亲则认为杀羊是雪豹的天性,打死雪豹会累积恶业。当地官员和警方之后陆续赶到,坚称雪豹是国家一级野生保护动物,必须放生。登场的人物还有“雪豹喇嘛”。小喇嘛是那个愤怒牧民的弟弟,对拍摄野生动物很感兴趣。随着叙事推进,他和处于矛盾中心的那只雪豹间的特殊关系也逐渐显现。

以动物保护为主题的影片不算少,比如陆川2004年的大热片《可可西里》就讲的是保护样貌可爱且对人类毫无威胁的羚羊免遭盗猎的故事。但不同于诸如《可可西里》的影片,《雪豹》讲述的故事更具挑战意味,因为电影并不回避雪豹作为肉食动物的天性。和万玛之前的作品相比,除了节奏更快、更引人入胜外,《雪豹》标志着万玛的诸多新尝试。首先,片中的雪豹是完全由CG技术制作的。从《静静的嘛呢石》(ལྷང་འཇགས་ཀྱི་མ་ཎི་རྡོ་འབུམ།,2002)到《塔洛》(ཐར་ལོ།,2015),万玛已建立起明确的现实主义美学风格,这种风格一般不涉及CG技术的使用。关于他先前的作品,万玛生前经常说,他想要在银幕上呈现他熟悉的西藏。他觉得自己在长大的过程中,一直被外人对西藏极不准确的描述所包围。这些描述中既有被理想化的香格里拉,也有被妖魔化的“封建神权”。因此实地拍摄、本土演员、藏语对白一直是之前万玛电影的特点。他让藏地演员以母语表演,这些演员的生活就充溢着中国西藏地区特有的现代与传统的复杂混合。而《雪豹》中大规模CG技术的使用表现出万玛探索新技术与新美学风格的意愿。

《雪豹》较万玛先前电影的第二大不同体现在影片对梦境、记忆,以及视角的运用。万玛由着重准确呈现西藏的外表转向了表达西藏的内里。他在《雪豹》之前完成的两部电影《撞死了一只羊》(ལག་དམར,2018)和《气球》(དབུགས་ལྒང་།,2019)已体现了这种变化。观看那两部电影时,观众有时并不清楚看到的视角是属于某个角色还是多个角色共享的。在万玛电影所刻画的藏族文化中,“转世”是人们习以为常的概念。他的角色不时会问,某个孩子是否为不久前刚去世的某人的转世。所以,也许这种主体性和共享的主体性间的模糊也是西藏内里的一部分。《雪豹》中,万玛的重大创新在于设置“雪豹喇嘛”和雪豹的链结,由此观众被带入人类与其他动物共享的记忆与主观视角。鉴于藏传佛教认为灵魂在众生间轮回转世,而众生包含一切有情识作用的生物,那一链结的设置也是万玛对西藏内在文化影像化呈现的一部分。

第三,相较万玛的其他电影,《雪豹》在处理中国境内藏区当代生活中的复杂关系和紧张态势时,前所未有地充分及坦率。作为中国首位藏族长片导演,万玛很清楚和西藏相关的一切都极度敏感,他也一直小心谨慎以确保自己的电影能通过电影局的审查。在其早期作品里,万玛会尽可能避免电影中出现藏汉之间的接触。遇到质疑,他会说,他的故事都设定在几年以前,都发生在汉人很少的地方。他在《气球》中探讨了较之前更为敏感的问题,涉及计划生育和这一政策的影响。可是,和之前的电影一样,《气球》中的主要角色,包括官员,都是藏人,而且几乎整部电影的对白都用的藏语。

《雪豹》则不同。一开始,影片就点出故事发生在2016年。这个时间具体又离当下并不遥远。以电视摄制组驱车前往牧民家中作为时长不短的开场可能会让一些观众想起万玛早年的一部电影《寻找智美更登》(འཚོལ།,2007)。尽管如此,二者差别显著,因为《雪豹》开头的对白是藏语和普通话混杂的。影片中的摄影师虽然想学藏语,但才刚刚入门。而他的藏族同事从小就学普通话,和他交流很容易。

《雪豹》全片充满张力。但是,尽管电影中既有藏人角色,也有汉人角色,那些张力并不源自族群间的冲突。族群不一的角色实际表现的是对世界不同的理解。政府官员和警察要维护《野生动物保护法》,他们中有藏人也有汉人。想打死雪豹的牧民最在意自己的经济损失,如果能得到等价九只羯羊的补偿,他就会放了雪豹。牧民的父亲和小喇嘛与上述角色的想法不同。他们不太关心眼前的经济或法律问题,而是关注人类和其他动物的相处之道,以及维系双方共同的生活世界所牵扯到的伦理。由此,《雪豹》不仅传达了藏族的文化逻辑,还与人类世下当代的生存危机极为契合。

从《雪豹》中可以看出,万玛才旦正处于创作高峰期,他敢于尝试新的叙事方式,探索新的电影形式。然而,在电影上映之前,他不幸于2023年5月8日去世,年仅53岁。我不清楚事情的全貌,但听说万玛可能是在为下部电影勘景时高山症发作,进而突发心脏病逝世的。值得玩味的是,《雪豹》中有很多时刻在表现角色攀登高峰时喘不过气,或是他们处在高海拔地区需要吸氧。我还听说万玛下部电影的素材可能已经准备好了。但如果《雪豹》是万玛最后一部电影,那无疑说明我们损失巨大。

展映信息:

万玛才旦《雪豹》(2023)将于2024年2月3日晚于在第二届薄荷紫华语电影节主场地Keswick Alhambra Cinema进行特别展映。

时间:2024年2月3日 周六晚20点

地点:凯西克阿罕布拉电影院 1号大厅(Keswick Alhambra Cinema, Screen 1)

电影节主场地:36 St John's St, Keswick CA12 5AG, UK