Review the Bodhi tree in Bosch's garden

Siria Falleroni

Heaven and earth

In the triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights, the Flemish artist Bosch depicts the Third Day of the

Creation of the World - when the waters were separated from the land and heaven was created - along with Adam and Eve, hell, and an artificial paradise, plunged into the same lust as the neighboring inferno. In Chinese mythology, however, it is the god Pangu who separates Heaven from Earth, his body transforming into rivers, mountains, plants, animals, and everything else in the world, including a powerful being known as Huaxu. Huaxu later gave birth to a twin brother and sister, Fuxi and Nüwa, two creatures with human faces and snake-like bodies.

Leopold Liu, the artist-father of the director, wants to plant a bodhi tree - the tree under which Siddhartha attained enlightenment - in the Garden of Earthly Delights, hoping it will give rise to the flower of a “new humanity”. This very act gives the name to Maia Liu’s experimental docufilm: The Bodhi Tree in Bosch’s Garden, currently part of the Feature Competition in the section ‘C-Film in Focus’ of the 3rd edition of “Mint Chinese Film Festival”. Buddhism, Chinese cultural heritage, Asia - planted within Bosch’s Garden, among Hell, Paradise, and the sins of Europe. But what is really the West, and what is the East?

It is precisely this contamination - a mutual cultural insemination - that forms the structural foundation of Liu’s work. In 2023, the director receives an email from her father, a man she barely knows, inviting her to explore his personal artistic archive, abandoned in an old house in Leuven. “I remember that you are very good at giving old stuff new lives” he tells her. In this descent into her father’s personal “inferno”, Liu is accompanied by her Chinese best friend, Yezi, just as Virgil accompanies Dante through Paradise, Purgatory, and Hell in The Divine Comedy.

Abandon your identity, negate yourself

In just forty minutes, this medium-length film unfolds on multiple levels, interwoven with the lives of three highly complex and layered characters. The first is the director herself, of Chinese descent but raised in Belgium, unfamiliar with the Chinese language or her father. The second is her father, an emigrated Chinese artist who is carrying with him the weight of his cultural heritage. The third character is Yezi, a Chinese girl living abroad, yet unable to fully belong to either China or Europe - a sort of third cultural hybrid between Maia’s experience and that of her father. Their experiences blend in a dance of footage that, at first glance, seems hastily and chaotically edited, but has its own logic.

On one side, we observe the father’s archival material: a visionary artist who dreams of a new

humanity, seeks to purify everyone with a staff, and is firmly convinced of the nonexistence of the

self: “Today it is impossible to know yourself anymore: the first step to know yourself is to negate

yourself. Address the multicultural conflicts; the problem comes from individual identity. Identity

does not exist: abandon your identity and negate yourself”, he exclaims in front of the camera.

In the movie, identity is an open wound that struggles to reimagine itself. While Leopold Liu denies it, Yezi and Maia attempt to explore it through the cinematic medium. They turn the camera on each other, reflecting themselves in one another, confronting each other through intense and intimate closeups.

The tenth symphony forgives the West

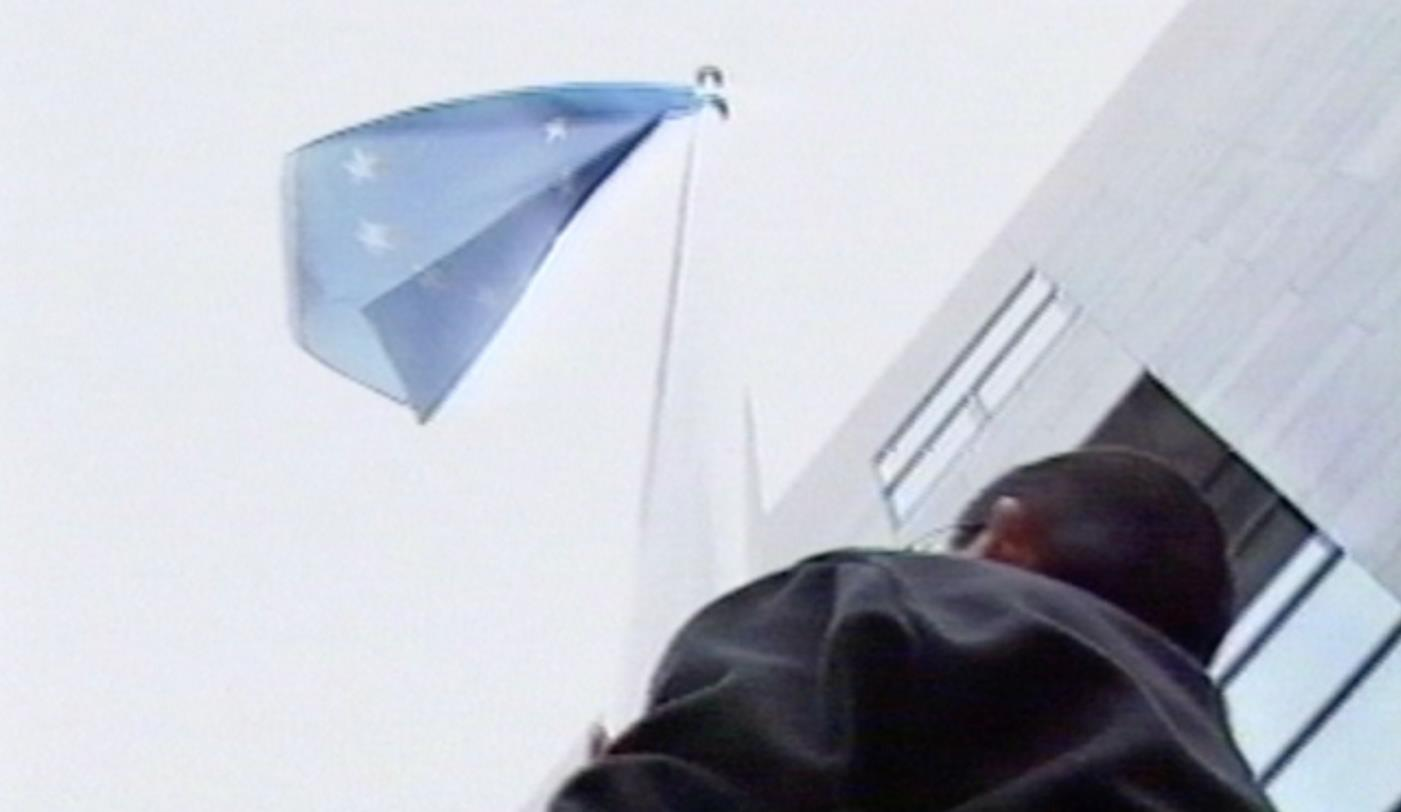

The exploration of one’s own identity inevitably leads back to the trauma of colonization and the role

of the West - if we can and must necessarily define it - in the personal experiences of the characters. In one of the many clips, we see Leopold climbing a pole where the European flag flies: a desperate yet futile attempt to reach an ideal that does not exist, as fictitious as Bosch’s painted paradise.

The two girls also discover that Leopold has stolen a wooden “summer flower” from a Chinese pavilion in Brussels, a structure commissioned by Leopold II (King of Belgium in the 19th century). Not only is there a parallel between the name of the Belgian king and the “Western name” of the director’s father, but this act also represents an attempt to reclaim something that feels legitimately “Chinese”. Leopold takes a tiny, insignificant object from a simulacrum, a bizarre Chinese pavilion built in a Belgian city, in an effort to reclaim a lost self, buried in cultural contamination. But what is most striking is the reaction of the two girls: Maia wants to return the wooden flower to the Brussels Museum, while Yezi is angered by her choice because she feels that this insignificant piece of art does not belong to them, to the museum, to the Belgians, or to Europe.

Yezi sees herself reflected in and understood by the same anger and fire that burns within Leopold Liu: they share the same bleeding wound in relation to the “West”. A compelling parallel emerges in their experiences of living in Europe. In an archival clip, Leopold says: "Europe to me was holy, but when I came here I found nothing”. Similarly, Yezi confesses to Maia that she understands the motivation behind colonization: “It’s so bleak here. If they don’t colonize, they are going to die. It’s just bleak. Nothing grows here”. Yezi and Leopold Liu realize they have both entered the Garden of Earthly Delights, only to find that it is merely an illusion: a barren land that bears no seeds. The climax of their defiance against the West reaches its peak in one of the final sequences. The two friends stand before one of the European Union buildings as Maia sets fire to a papier-mâché camera: the fire of anger finally ignited. But soon after, they grow frightened by their act and extinguish the small blaze. All that remains is smoke, and Yezi, silent, watched by men in suits who observe her without comprehension.

In short, through laptop screen recordings, iPhone footage, Sony a6700 footage, and archival material, Maia Liu creates an extraordinarily complex work that delves into identity, art, colonialism, and the meaning of being Chinese outside of China.

Siria Falleroni

Insta: @siriafalleroni

She/she

Siria Falleroni graduated in Chinese language and culture from the University of Venice, where she worked for three years in a row at the Venice International Film Festival. She has participated in various film festival juries and critic workshop, such as Brussels International Film Festival and Five Flavours Asian Film Festival in Warsaw. Her main areas of interest include East Asian cinema with a focus on China, documentaries and independent cinema.